DIRE Warnings, Part 2: A Diversity of Definitions

How Diversity, Inclusion, Representation, and Equity are supposed to work and where they go wrong.

This article is Part 2 in a series. Part 1 summarized what the series will demonstrate.

A Diversity of Definitions

As a starting point to illustrate the problem addressed in this series, let’s look at an example definition for equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in practice (Figure 1).

A key feature is the definition of diversity as “differences in race, colour, place of origin, religion, immigrant and newcomer status, ethnic origin, ability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and age”. Contrast this with the definitions in Figure 2 from a training course, Diversity and Inclusion Fundamentals, prepared by the Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion (CCDI).

The CCDI training course makes use of fictionalized stories, in this case involving two characters, Tara and Matt. They also use a model of personal identity in which traits are divided into four categories, layers, or dimensions. The lessons in the training course are not reliant on the model or dimensional categories, but this format is useful to make reference to types of traits.

Some key things to note about the CCDI definition of diversity:

Diversity is about the individual.

Diversity is not just about visible characteristics (e.g., race, gender)

Diversity refers to the variety of unique dimensions, qualities, and characteristics within individuals, not a measure of one characteristic between individuals.

Personality is the core of diversity. (In the model they use, this is Layer 1.)

While immutable traits, disabilities, and disorders contribute to diversity within an individual (Layer 2), diversity also includes more controllable characteristics (Layer 3) such habits, beliefs, marital status, education, experience, parental status, and other situations and life experiences, as well as occupational and organizational components (Layer 4).

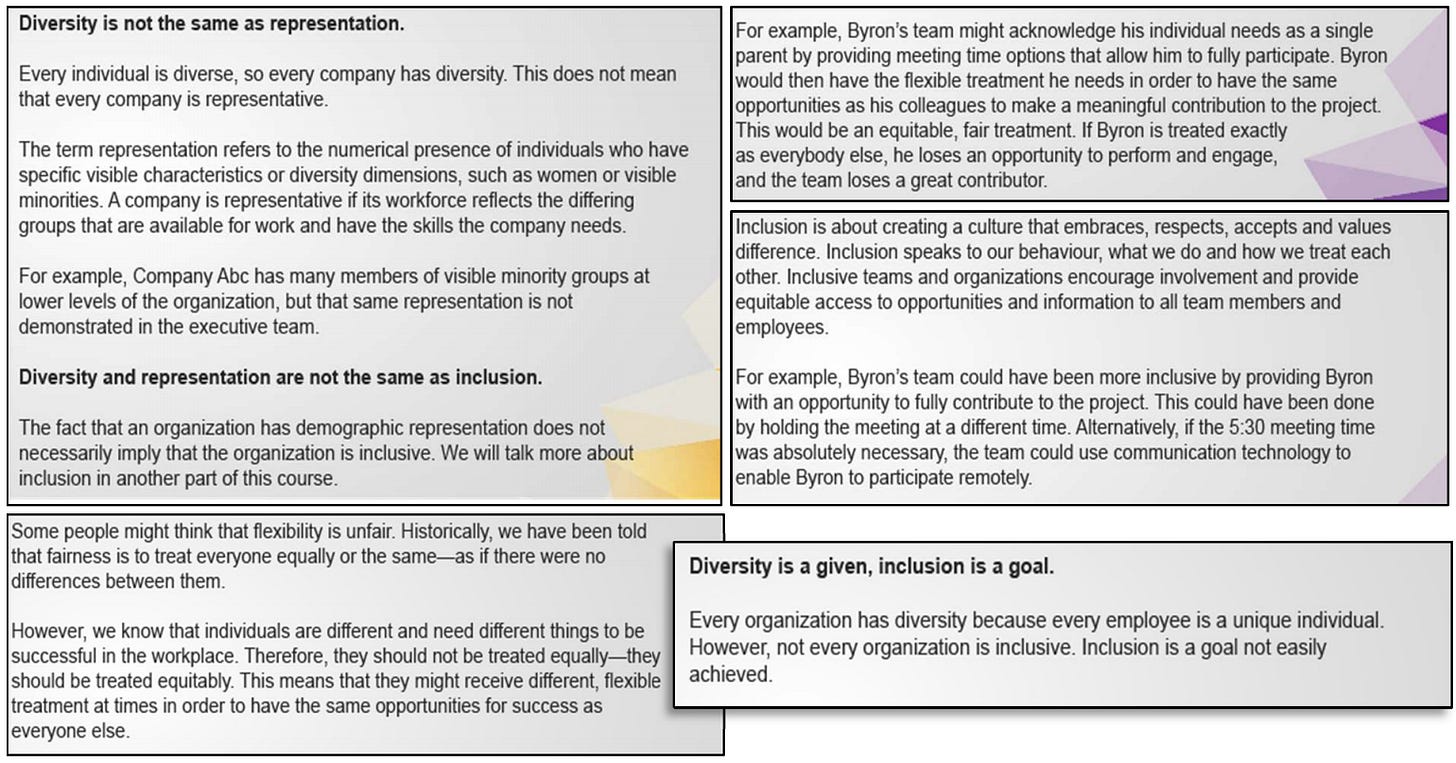

The CCDI training also notes that diversity is often confused with other concepts (Figure 3):

Diversity is not the same as representation. Representation is the numerical presence of individuals who have specific visible characteristics, such as women or visible minorities. (This is discussed in a later article in this series as it appears to be a key confusion point.)

Diversity is not the same as inclusion. Inclusion is creating a culture that embraces, respects, accepts and values difference and the diversity within each individual team member. Inclusion is in opposition to an assimilative mono-culture that has one way of doing things and excludes other approaches.

Every organization has diversity because every employee is a unique individual.

The goal is for organizations to be inclusive, meaning to value and respect the diversity within each individual, meaning to value and respect unique dimensions, qualities, and characteristics that we all possess and bring to the job.

So what can organizations do to promote diversity and inclusion? The CCDI training has that covered (Figure 4):

Promote respect for individuals.

Acknowledge the diversity in individuals, not pigeonholing them into a single category.

Learn more about individuals.

Question assumptions you make about other people’s background and values, where much discriminatory behaviour and stereotypes come from, even if intended positively.

Advocate for different perspectives, new ideas, and new ways of doing things – including from people who aren’t new to the organization.

Be flexibility to accommodate the needs of individuals to do their job effectively.

Use technology to support individuals where possible.

Re-frame your perspectives to recognize the accommodations being made for most people, such as chairs and lights that are not needed by everyone to do their job.

Notice the significant difference between the diversity (and inclusion) as defined and applied in the CCDI training and the misconceptions used in practice (Figure 1). These are not mere semantic differences, but almost complete opposites in concepts and resulting policies.

Misconceived EDI uses one dimension (Layer 2) and applies it to head-counting within org charts. Conversely the CCDI training says to avoid treating people on one dimension and instead treat people across all of their dimensional layers. EDI is about treating people as whole individuals. Treating them as a singular trait and as an additional unit toward a head-count target is the exact opposite of EDI.

There are important reasons why the definitions and recommendations in the CCDI Diversity and Inclusion Fundamentals training course are core to how EDI works and why the Misconceived EDI versions are problematic and predictive of inevitable failure. These reasons fall into categories of EDI value, law, psychology, and engineering design. Exploring these reasons is the core of this series of articles.

Valuing Diversity and Inclusion

According to the CCDI, the value of diversity and inclusion to organizations is found in the performance of teams, organizations, and businesses (Figure 5). It is the variety of ideas, approaches, and ways of thinking that brings about this value, as opposed to a mono-culture doing things the same way as always or limiting the selection of employees through inadvertent barriers and other unnecessary exclusions.

Note that these values are not specific to a single dimension of diversity. The pool of talent could be unnecessarily limited by race or gender based on hiring and retention practices, but could also be limiting the hiring of introverts, single parents, or people with the right skills but via a different educational route than typical.

The value of diversity results from a wider range to draw from, whether is a wider talent pool, wider set of ideas, wider set of informational knowledge, wider set of skills and experiences, or wider set of personality traits1 2 3 4 5 6. The value doesn’t come directly from people looking different from each other, nor does that hurt. The research of Elizabeth Mannix, from Cornell’s Johnson Graduate School of Management, and Margaret Neale, Professor of Organizations and Dispute Resolution at Stanford Graduate School of Business, addresses the dimensions its value comes from7:

“As we disentangle what researchers have learned from the last 50 years, we can conclude that surface-level social-category differences, such as those of race/ethnicity, gender, or age, tend to be more likely to have negative effects on the ability of groups to function effectively. By contrast, underlying differences, such as differences in functional background, education, or personality, are more often positively related to performance—for example by facilitating creativity or group problem solving—but only when the group process is carefully controlled.”

Be careful to note that this is not a position against building teams with differences across social categories like race/ethnicity, gender, or age (Layer 2). The net effect of such teaming is neutral to positive8. Rather the point is that the value of diversity to the function of the team and organization does not come from surface-level differences or Layer 2 traits per se; it comes from underlying informational differences such as culture, functional background, and education (Layer 3), or personality (Layer 1)9 [2][3]. From (Goins & Mannix, 1999)[9]:

“Linking composition to group process and performance, we find that ethnic diversity decreased similarity of work values but did not affect group performance, which is primarily predicted by satisfaction and conflict.”

Meta-analysis of 108 empirical studies covering 10,632 intra-national and cross-national diverse teams found neutral outcomes with respect to multi-cultural traits but positive with respect to providing additional information in the form of novelty of ideas [8]:

“These findings suggest that the presumed greater divergence in values, beliefs, and national identities in multicultural/multinational teams per se does not necessarily lead to more positive or negative effects on team processes and performance outcomes, relative to those in single-country diverse groups.”

“[T]he meta-analysis results supported the assertion that greater cultural diversity in teams had a positive impact on creativity. Creativity was assessed in terms of the novelty of ideas generated on a brainstorming task, the ability to generate creative solutions to problems or case studies, or the development of creative endings of short stories.”

Moreover, it is important to focus on the value of informational diversity resulting from different social categories rather than focusing on the immutable traits of those (Layer 2) social categories [2]:

“Increased productivity, creativity, and enhanced morale depends not only on the presence of diverse viewpoints and perspectives but also on the effective management of the conflict that arises due to these forms of diversity and the smooth implementation of the new and improved ideas.”

“Teams that focus on differences in individual's work experience, educational training, and functional expertise (informational diversity) are able to debate constructively in an accepting setting (task conflict). However, teams that focus on differences in gender, race, and age (social category diversity) are more likely to stereotype and interpret things in a personal manner that is often destructive (relationship conflict). Teams that hold similar values about work and group goals are much less likely to debate about resource and work allocation (process conflict) and less likely to engage in personal attacks (relationship conflict).”

Social-category (Layer 2) diversity does appear to provide value in increased satisfaction, intent to remain, and commitment [1][8] and in making the team more prepared for handling conflict10:

“[D]iversity across dimensions, such as functional expertise, education, or personality, can increase performance by enhancing creativity or group problem-solving. In contrast, more visible diversity, such as race, gender, or age, can have negative effects on a group—at least initially.”

“’In fact, the worst kind of group for an organization that wants to be innovative and creative is one in which everyone is alike and gets along too well,’ she says. And the key to making nearly any kind of diversity work is managing it well.”

“’One of the most interesting recent findings in the area of work-team performance is that the mere presence of diversity you can see, such as a person’s race or gender, actually cues a team in that there’s likely to be differences of opinion. That cuing turns out to enhance the team’s ability to handle conflict, because members expect it and are not surprised when it surfaces.’ A more homogeneous team, in contrast, won’t handle conflict as well because the team doesn’t expect it. ‘The assumption is that people who look like us think like us, but that’s usually just not the case.’”

“It’s group conflict that actually makes a team function with more of the razor’s edge it needs to be innovative. ‘Of course, we’re talking about intellectual conflict, debate, and controversy, not personality conflict.’”

“One ramification of the finding that diversity stirs up the pot in healthy ways is that managers need to rotate the composition of their groups periodically to keep things fresh. But newcomers to the team should be different in some critical way, be it in an area of expertise, level of education, manner of thinking, or some similar dimension.”

“Neale suggests managers purposefully assign roles such as “devil’s advocate,” or “cheerleader,” and occasionally switch around those roles.”

“While it may seem paradoxical, one way to foster cooperation is to create an atmosphere in which dissenting views can be freely aired. “The minority viewpoint, whatever that may be, and whether it comes from a person who looks different or not, needs to be supported”

To be even more specific, the research indicates that it is informational diversity that is key11:

“People tend to think of diversity as simply demographic, a matter of color, gender, or age. However, groups can be disparate in many ways. Diversity is also based on informational differences, reflecting a person’s education and experience, as well as on values or goals that can influence what one perceives to be the mission of something as small as a single meeting or as large as a whole company. Diversity among employees can create better performance when it comes to out-of-the-ordinary creative tasks such as product development or cracking new markets, and managers have been trying to increase diversity to achieve the benefits of innovation and fresh ideas.”

“It turns out that different types of diversity generate various sorts of conflict, which affects how a team performs. The kind of group conflict that exists and how the team handles the conflict will determine whether this diversity is effective in increasing or reducing performance.”

“The researchers found that informational diversity stirred constructive conflict, or debate, around the task at hand. That is, people deliberate about the best course of action. This is the type of conflict that absolutely should be engendered in organizations. On the other hand, demographic diversity can sometimes whip up interpersonal conflict. This is the kind of conflict people should fear. “People think, ‘I have a different opinion than you. I don’t like what you do or how you do it. I don’t like you,’” says Neale. “This is what basically can destroy a group.””

“The third type of diversity is based on goals and values, and it actually generates both types of conflict. This is the most potentially damaging of all the diversities. Without value-goal homogeneity, a team can accomplish little.”

From a causal perspective, the informational diversity does not provide the value directly, but via informational conflict [1]. Conflict based on social categories (Layer 2) and value-based conflict reduces performance, satisfaction, and intent to remain.

To summarize this research, value comes from informational diversity combined with seeking differing views and debate. This is consistent with CCDI (Figure 4): “Be an advocate of different perspectives. Value new ideas, new people and new ways of doing things – including when innovation comes from people you currently work with, who aren’t necessarily “new” to your organization!”

Informational conflict and debate are critical to innovation, creativity, and functional success of teams. Surface-level social categorization (Layer 2) trait variability has little effect one way or the other, with several minor positive values. The exception is that actively focusing on the immutable traits of social categorization such as race, gender, and ethnicity has a very negative effect in interpersonal conflict. It is better to not focus on Layer 2 surface-level characteristics at all and instead focus on the informational diversity.

To reiterate, this does not mean to avoid creating teams of mixed race, gender, or ethnicity, but rather not to focus on those differences as being important to the team. Instead, focus on these differences with respect to information diversity which includes different cultural backgrounds and life experiences. Of course, these will correlate with surface-level visible traits, but it is the different cultural information that matters. The research clearly shows that organizations should protect against tribalizing people along the lines of social categories or political leanings as those result in dysfunctional teams and organizations. (The threat of tribalization is discussed in greater detail later in this series.)

These types of results are consistent across the literature and are consistent with the value of diversity and inclusion in Figure 5, mirrored in how to value diversity in Figure 4, and noting personality as core to diversity in Figure 2, all from the CCDI Fundamentals of Diversity and Inclusion training course.

The CCDI training further notes improper ways of valuing diversity and inclusion. The course recognizes common misconceptions about EDI by starting participants with an org chart and photos and asks them to evaluate the organization’s success at diversity and inclusion. The conclusion of the course, shown in Figure 6, notes that you cannot evaluate EDI based on org charts, head-counts, or one-dimensional visible characteristics. Rather, EDI is evaluated on the processes of how people’s input is valued and included, the removal of unnecessary barriers internally and in hiring practices, and the flexibility of the organization to the needs of individuals within the organization12.

From Iris Bohnet, the Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government and Academic Dean of Harvard Kennedy School13,

“Many companies evaluate their employees based on past performance, but also on future potential. And, of course, by definition performance is backwards looking and therefore more easily measureable and quantifiable. So we tend to see fewer biases being able to creep in there. But when we think of potential, of course that’s wide open an that’s where we fill in the blanks with the stereotypes of what a typical leader looks like or the kinds of people who have made it in our organization.”

“We have to move beyond trying to fix our mindsets in diversity training programs or fixing the traditionally underrepresented groups, whether this is women or people of colour or other excluded groups and get into our practices and procedures and de-bias how we hire, how we evaluate people, how we promote people, how we organize our meetings.”

The CCDI training and research literature agree on this; the goal of EDI is to address organizational barriers, not re-training people’s thinking or targeting statistical outcomes based on immutable traits.

This does not mean Layer 2 social categories are unimportant or ignored. Quite to the contrary, they are part of who we are and the diversity we each bring. Figure 6 provides a means to address Layer 2 traits and head-counts via representation. Figure 3 noted these terms can be confused and clearly defined representation as “the numerical presence of individuals who have specific visible characteristics or diversity dimensions, such as women or visible minorities.” That does sound much closer to the Figure 1 misconceived definition for diversity. However, representation also comes with a set of constraints as far as law, psychology, and engineering design.

Part 3 of this series will address legal and psychological ramifications of Misconceived EDI. Part 4 will address representation.

Neale, M. A., Northcraft, G. B., & Jehn, K. A. (1999). Exploring Pandora's Box: The Impact of Diversity and Conflict on Work Group Performance. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 12(1), 113-126. doi:10.1111/j.1937-8327.1999.tb00118.x

Jehn, K. A. (1999). Diversity, Conflict, and Team Performances Summary of Program of Research. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 12(1), 6-19. doi:10.1111/j.1937-8327.1999.tb00112.x

Thatcher, S. M. (1999, March). The Contextual Importance of Diversity: The Impact of Relational Demography and Team Diversity on Individual Performance and Satisfaction. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 12(1), 97-112. doi:10.1111/j.1937-8327.1999.tb00117.x

Mannix, E., & Margaret, N. A. (2005). What Differences Make a Difference. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31-55. doi:10.1111/j.1529-1006.2005.00022.x

Wilde, D. (2010, February 1). Personalities into Teams. ASME Mechanical Engineering Magazine, 132(2), pp. 22-25. doi:10.1115/1.2010-Feb-1. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/memagazineselect/article/132/02/22/380041/Personalities-into-TeamsWe-Take-Different

Winsborough, D., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2017, January 25). Great Teams Are About Personalities, Not Just Skills. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2017/01/great-teams-are-about-personalities-not-just-skills

Phillips, K. W., Mannix, E. A., Neale, M. A., & Gruenfeld, D. H. (2004). Diverse groups and information sharing: The effects of congruent ties. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40(4), 497-510. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/facultyresearch/publications/diverse-groups-information-sharing-effects-congruent-ties

Silberzahn, R., & Chen, Y.-R. (2012). Toward Better Understanding of Interaction Dynamics in Multicultural Teams: A Status Perspective. (M. A. Neale, & E. A. Mannix, Eds.) Research on Managing Groups and Teams (Looking Back, Moving Forward: A Review of Group and Team Based Research), 15, 327-357. doi:10.1108/S1534-0856(2012)0000015016

Goins, S., & Mannix, E. A. (1999). Self-selection and Its Impact on Team Diversity and Performance. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 127-147. doi:10.1111/j.1937-8327.1999.tb00119.x

Rigoglioso, M. (2006, August 1). Diverse Backgrounds and Personalities Can Strengthen Groups. Insights by Stanford Business. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/diverse-backgrounds-personalities-can-strengthengroups

Stanford GSB Staff. (1999, November 1). Diversity and Work Group Performance. Insights by Stanford Business. Retrieved June 24, 2021, from https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/diversity-workgroup-performance

Bohnet, I. (2016). What works : gender equality by design. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Retrieved 2021, from https://scholar.harvard.edu/iris_bohnet/what-works

Bohnet, I. (2018). Women's Voices - Iris Bohnet [Motion Picture]. Retrieved June 25, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tOIB6Dw-M